[ad_1]

Throughout history people have been looking for answers and salvation, seeking the assistance of the gods, the spirits of nature, and looking to them for help. When looking for answers about what lay in the future, they used divination. Oracles and shamans, elders and magicians, would look for symbols and clues in the oddest of places. From the study of animal intestines all the way to the observation of birds, the methods for divination were many. But, one of the most interesting is molybdomancy – the casting of molten lead.

Where Did Molybdomancy Originate?

Divination is one of the oldest ritual practices in the world. Its many diverse methods were present in virtually every culture and civilization in history, and were used for various purposes. The world itself originates in Latin: the word divinare means “to foretell, prophesy, foresee, predict.” Usually, the person performing divination had a special status; these were often shamans, village elders, priests, or occult practitioners. Not everyone was able to read the signs of divination. One had to possess a certain knowledge in order to interpret them – a link with the gods and the portents they brought.

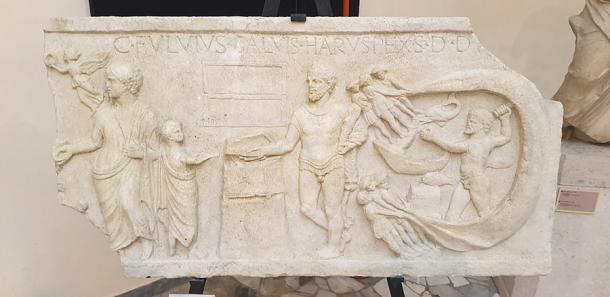

Numerous methods of divination were documented throughout history. In ancient Rome, it was common for high-ranking priests to observe what were known as auspices. Auspices consisted of observing the flight of birds in order to interpret it and discover the will of Jupiter. Others dealt with the method of divination called haruspicy. This consisted of examination of the entrails of animals sacrificed to a certain deity. A haruspex, specially trained to do so, sought favorable signs within the shapes and patterns of the entrails.

Early Slavs, for example, had a unique method of divining. They relied on horse divination to find answers to crucial questions. Either purely white or purely black, stallions would be led to sacred grounds and their actions observed. They would be led over spears, and if no spear was trod upon, the omens were good. Then again, other cultures practiced rare and brutal divination methods, such as observing the spasms of dying men in order to foresee future events and seek good omens. Other methods relied heavily on the sacrifice of humans and animals.

Relief depicting a haruspex from the Roman Temple of Hercules. (Jamie Heath / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Searching for Shapes in Molten Lead

Luckily, molybdomancy is not at all so brutal or cruel. Perhaps that is the reason why it has survived for longer and can still be observed amongst some cultures in the world. Molybdomancy, put in the simplest terms, is the pouring of molten lead into cold water. Upon contact, the lead instantly solidifies. The resulting shapes are always unique and irregular, offering a variety of options for interpretation. The word comes from Greek: molybdos meaning “lead”, and the suffix comes from manteia, meaning “divination”.

The overall divination process itself is almost always the same. Lead – and sometimes tin – pieces are melted in a spoon or a ladle over a flame. Often, the lead is already shaped: for example keys, horseshoes, and ships are common symbols, and can dictate the nature of the divination. Once melted in the ladle, the liquid metal is poured into water – often in a ritual procedure.

When the hot liquid comes into contact with the cold water, it instantaneously becomes solid. However, due to the chemical reaction, the lead takes on a severely distorted shape. The result can never be predicted and it is always unique. As such, it can often resemble certain shapes or patterns ideal for interpretation.

These shapes are interpreted symbolically. The diviner or oracle observes the shapes and looks for symbols that can be related to the person seeking answers or an insight into the future. For example, if the surface was covered with small bubbles, that would be the indication of material wealth in the future. On the other hand, a very thin, fragile, or broken shape would be a clear indication of future misfortune. Often enough, if the shapes are unclear, the lead piece would be held before a candlelight, and the shadows it cast would be interpreted instead.

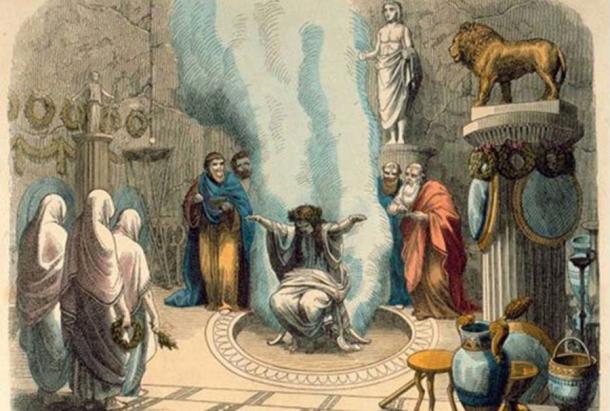

„Delphic Oracle“ from ancient Greece in a painting by Heinrich Leutemann. ( Public domain )

From Ancient Greece and Across the Globe

Molybdomancy was actively used across history. Scholars agree that this practice of divination – which was available to all – originated in ancient Greece . From there, it spread throughout the civilized world, reaching Central Europe where it caught on amongst the Slavic and Germanic peoples of later centuries. Eventually, it became common in Scandinavia, and the British Isles.

During the Middle Ages, molybdomancy was used as a divination to see if there was illness in a patient and also for medical prognosis. During this time, lead was seen as a negative symbol and was usually associated with death, since exposure to high amounts of lead, known as saturnism, can cause severe poisoning, affecting the brain and potentially causing death.

In the 1500 and 1600s it was popular to divine with molten lead in order to check for bewitchment. It was thought that a person’s illness could be caused by a witch, so the divination was used to see if this was the case. Over time, the practice didn’t die out, surprisingly. It survived in mostly rural regions of Europe, as a folk tradition.

In 19th century England and Wales, it was popular for young women to use molybdomancy as a way to foretell the future for their husbands, to discover if they would be wealthy and successful. This ritual was carried out either at Midsummer or on All Hallow’s Eve, a clear indication that the practice is a long-surviving pagan custom.

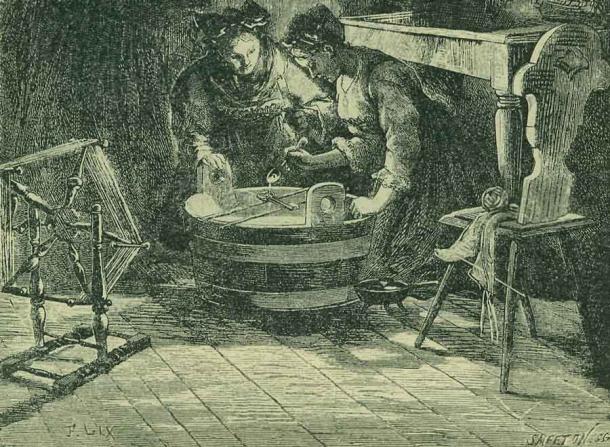

Casting lead with a spoon from an illustration by J. Dotřela. ( Public domain )

Traditions of Molybdomancy in the Balkans

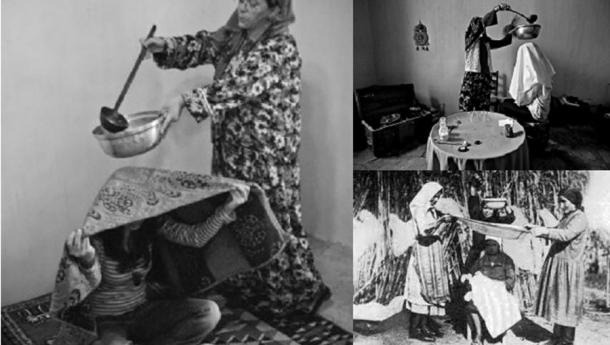

It also survived in the rural Balkans, and is actively used to this day. In rural Serbia, it is known as саливање страве or саливање страха. Both terms roughly translate as “pouring of fear” and are used as a way to discover what troubles or affects young children, and sometimes adults too. The ritual usually involves a woman colloquially called a sorceress, witch-woman, fortuneteller, seer, and similar.

This woman performs a complex ritual seeped in old pagan Slavic folklore, pouring the molten lead over the child’s head and into the cold water. The resulting shapes are interpreted as something that might be the cause of the child’s “fear”, meaning its sickness, frailty, insomnia, illness, restlessness, and so forth. The solidified lead then needs to be thrown into a fast-flowing river, so it would take away the child’s fears, which are now trapped in the solidified lead. This custom is also present across the Balkans, notably in Bosnia.

A similar ritual exists in Turkey. It is called kurşun dökme (literally “lead pouring”) and also involves a woman pouring lead over a person’s head. The ritual is used to help with spiritual problems, illnesses, and fears, but is also used to predict the future and observe potentially beneficial symbols.

Kurşun dökme is the Turkish tradition of molybdomancy, or lead pouring. (Dontbesogullible / CC BY-SA 4.0 )

Lead Casting as a Measure Against Huldrabarn Fairy Changelings

Molybdomancy holds an important place in the folk traditions and customs of Norway. There, it is known as “støyping”, meaning “casting”. This custom was one of the most important aspects of “trolldom”, the Norwegian magical folk tradition that is variously translated as witchcraft, sorcery, and magic.

In Norway, lead casting was done a bit differently. In the ritual, a woman would use either lead or tin for the purpose, but most sought after was lead scraped from church windows or church bells as it was believed it had the holiest and most powerful properties. Once melted, this church lead, known as “church metal”, would be poured through a hole made in a piece of barley flatbread . Below the bread was a bowl filled with cold water. In certain parts of Norway this had to be water drawn from a north-running stream or river.

Most often, the ritual was used to determine the cause of rickets in young children. Rickets is a condition that causes bowed legs, weak bones, and other problems. In rural Norway of old times, it was believed that rickets were a clear sign of a changeling, a fairy child left in place of the abducted human child.

In Norway, such creatures were called huldrabarn or bytting, and were left behind by the malicious forest creatures known as Huldra-folk. By observing the lead casting, the elderly woman diviner would conclude whether such a supernatural creature caused the child’s illness. Such a woman was called a signekjerring, the “blessing crone”. Furthermore, the water that was used in the støyping ritual was considered curative in and of itself.

Cartoon depicting molybdomancy in Germany. ( Public domain )

A Classic New Year’s Eve Quest for Good Luck Symbolism

In Finland, molybdomancy also survived up until the present day. However, it took on a more benevolent and somewhat festive character. It is known as uudenvuodentina, and is quite a popular tradition. The lead is cast for luck, and symbols are sought in the resulting shape.

Across Finland, shops sell packets with ladles and small lead pieces, usually in the shape of a horseshoe – a symbol of good luck. This is a popular New Year ’s gift, as people cast their horseshoe-shaped lead pieces and hope for a symbol of good luck for the coming year. The largest such lead piece was cast in 2010, and weighed in at 41 kilos (90 lbs), being the world’s largest New Year’s tin piece ever poured.

A similar tradition exists in Germany and Czech Republic. In German-speaking lands, it is called Bleigießen (“lead pouring”), and is performed on New Year’s Eve, as a way to foresee the future and find signs of good luck. Lead casts are observed for symbols of animals, structures, shapes, and common objects.

Shapes of cattle would mean prosperity, a chair would signify a new addition to the family, a clover would be a sign of great luck, a coffin would mean death or misfortune, an elephant would mean good health, gallows were seen as good luck, while serpents were seen as bad luck and illness. Many such shapes and their various interpretations exist. However, recent laws limit the sale of New Year lead casting kits, considering them as toxic lead-containing products.

A Serious Affair or a Simple Case of Pareidolia?

In the end, molybdomancy is a classic example of pareidolia . Pareidolia is a natural tendency of human perception to “impose a meaningful interpretation on a nebulous visual stimulus.” In simpler terms, this means that humans have a natural tendency to see shapes, objects, patterns, and symbols – where there are none. The usual examples include seeing shapes in the clouds, in fire, smoke, the tree canopies, or any other irregular natural patterns, and giving them meaning.

The casting of lead, molybdomancy, is not at all that different. A diviner consciously looks for images and symbols where there are none, and gives them a meaning. In ancient and medieval times, when beliefs and common knowledge were somewhat limited, this was seen as a potent omen. But nowadays, it can be considered as little more than a superstitious folk custom. Nevertheless, as such, it gives us an insight into the oldest folk traditions that were practiced across the world – shared unconsciously amongst many diverse cultures.

Top image: Woman practicing molybdomancy for New Year’s Eve. (Source: Gina Sanders / Adobe Stock

By Aleksa Vučković

References

De Givry, G. 1971. Witchcraft, Magic & Alchemy. Courier Corporation.

Della Sala, S. 2007. Tall Tales about the Mind and Brain: Separating Fact from Fiction. Oxford University Press.

Fiery, A. 1999. The Book of Divination. Chronicle Books.

Seidel, L. J, and Ciraolo, J. L. 2002. Magic and Divination in the Ancient World. BRILL.

Struck, P. 2018. Divination and Human Nature: A Cognitive History of Intuition in Classical Antiquity. Princeton University Press.

Stokker, K. 2007. Remedies and Rituals: Folk Medicine in Norway and the New Land. Minnesota Historical Society.

Unknown. No date. Bleigießen – Let Lead Reveal Your New Year’s Fortune. Sunny Side Circus. Available at:

https://www.sunnysidecircus.com/countries/germany/customs-traditions-germany/bleigiessen-fortune-telling-new-year/

[ad_2]

Source link